By C. Robert Mills, Jr.

I’m pretty certain that anybody reading this article who earned their seaplane rating at Philadelphia Seaplane Base, knows that the J-3 Cub or C-140 that they flew was launched and recovered much like a trailer-able boat. The plane—on its wheeled dolly—was simply pushed down an earthen ramp into the water until it floated off. Recovery was merely reversing this process.

But this was not always the case. During my time growing up at the Base (9N2) in the 1960s and 70s, the earthen ramp was only used for amphibious aircraft. We had a Grumman Widgeon, several Republic Seabees, and a couple beautiful Cessna’s on amphib floats based there at the time. For “straight-float” planes, my dad, C. Robert “Bob” Mills, used an ingenious system that dated from an even earlier time (built in 1916).

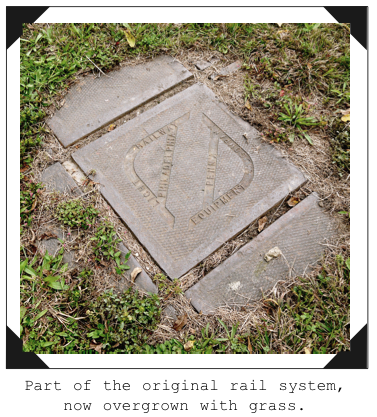

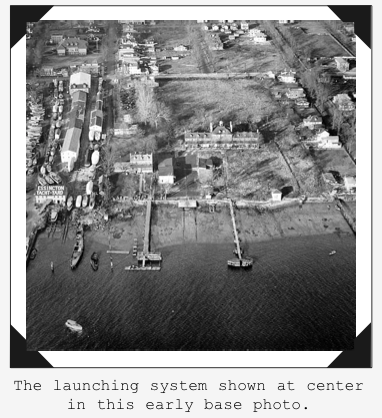

The Base hangars were laid out as two parallel rows facing each other. Between these rows was a wide green lawn that stretched down to the bank of the Delaware River. Embedded in this lawn were steel tracks, like a small railroad, about 3 feet wide. A spur track ran out of each hangar to the main track, which stretched the length of the lawn to the water’s edge. The planes were hangared on dollies that were fitted with railroad-style steel wheels that fit precisely on to the steel track.

The plane was pushed (by man or kid-power) out of the hangar, along the spur to a steel turntable at the main track. The plane was then heaved around 90º until the turntable lined up exactly with the main track. Now the plane could be pushed down toward the river.

So far, so good…unless you made the mistake of not lining the turntable up precisely with the track! The dolly, with the plane onboard, would roll off into the grass. Then out came crowbars, jacks, or usually all onlookers; to provide leverage to lift the whole rig back on to the track. Under my Dad’s tutelage, this mistake was NOT usually repeated.

Once the airplane was at the water’s edge, the plane, still on its dolly, was rolled slowly on to a ramp just past the end of the railroad track. We then manually lifted the plane’s tail, and pulled the dolly out back on to the track. Now the plane’s pontoons were sitting directly on the steel platform of the launching ramp. The fun was about to begin!

This launching ramp consisted of a steel framework covered by wooden beams. The steel platform noted above was mounted in the center of the ramp. The ramp was mounted on two steel tracks—like a continuation of the system I described to get the airplanes to the water, but much larger. These steel tracks were built upon wooden supports that were driven into the river bottom, and the track extended on a gentle downward slope about 150 feet out from the riverbank. Launching was accomplished by a combination of gravity, the plane’s propeller thrust, & usually a crowbar for that final bit of leverage to get the ramp rolling. The ramp was sent down the tracks until it was submerged, and the plane eased gently into the river, under control of the pilot. At least it worked that way most of the time…

This procedure was done many, many times, day after day, year after year, without incident…but there were some lessons to be learned, and occasionally an expensive one.

During launching, the pilot had to be careful not to gun the engine too much, lest he launch himself prematurely off the ramp, dropping 4 feet into the river mud! The ground crewman had to position himself properly so that he stayed on shore, and did not inadvertently ride the ramp down into the water after that shove with the crowbar. Also, after getting the ramp in motion, he had to immediately move to the winch brake to control the speed of the ramp as it descended. Having the ramp jump off the track was NOT an option.

Recovering the plane on to the ramp was the most challenging operation. As the plane approached the partially submerged ramp, the pilot had to apply enough power to get the plane firmly on to the ramp, but not so much as to keep going and fall off the other end! A system of wire rope (cable) and pulleys connected the ramp to a winch on shore. An electric motor powered the winch for recovery.

Unfortunately, I once observed a C-170 pilot with very little experience with our ramp apply too much power. Not only did the plane overshoot the ramp, it came to rest with pontoons straddling the steel track. Ouch! I don’t know which was worse, the damage to the plane or the dressing-down that pilot took from my Dad (his mantra was that a seaplane pilot operates under less than ideal conditions at all times, and should be prepared for them). Still, I have to say that ramp was a challenge for anybody’s skills.

And, as if the ramp was not challenging enough, up to now, we have assumed that a helper was available to control the ramp, either by the brake or the electric winch. But on many occasions, there was no help (“solo” does not apply only to flying). Now, after a harrowing, but successful taxi on to the ramp, you find yourself sitting 150 feet out into the river wondering how you are going to get yourself, your plane, and that ramp back to shore.

The solution is staring right at you, as you see that narrow ribbon of steel track extending all the way to shore. You have now become, in addition to an airman, a tightrope walker! The perils are present, but not deadly. You could lose your balance, and end up with that steel track firmly between your legs. Or, more likely, you fall off and are covered with mud due to the low tide. Hey, at least you didn’t drown or swallow any of the Delaware’s well-known water. And you didn’t spend hours waiting in vain for help to arrive.

In fact, you have achieved a rite-of-passage by “walking the track” to get to the winch house. Now, before you bask in the glory of your success, remember, don’t let that ramp hit the seawall too hard as you winch it back home. And by the way, you still have to put the airplane back in the hangar—without help!